4 Parallel Processing Techniques in Python

...explained with code!

Training LLM Agents using RL without writing any custom reward functions

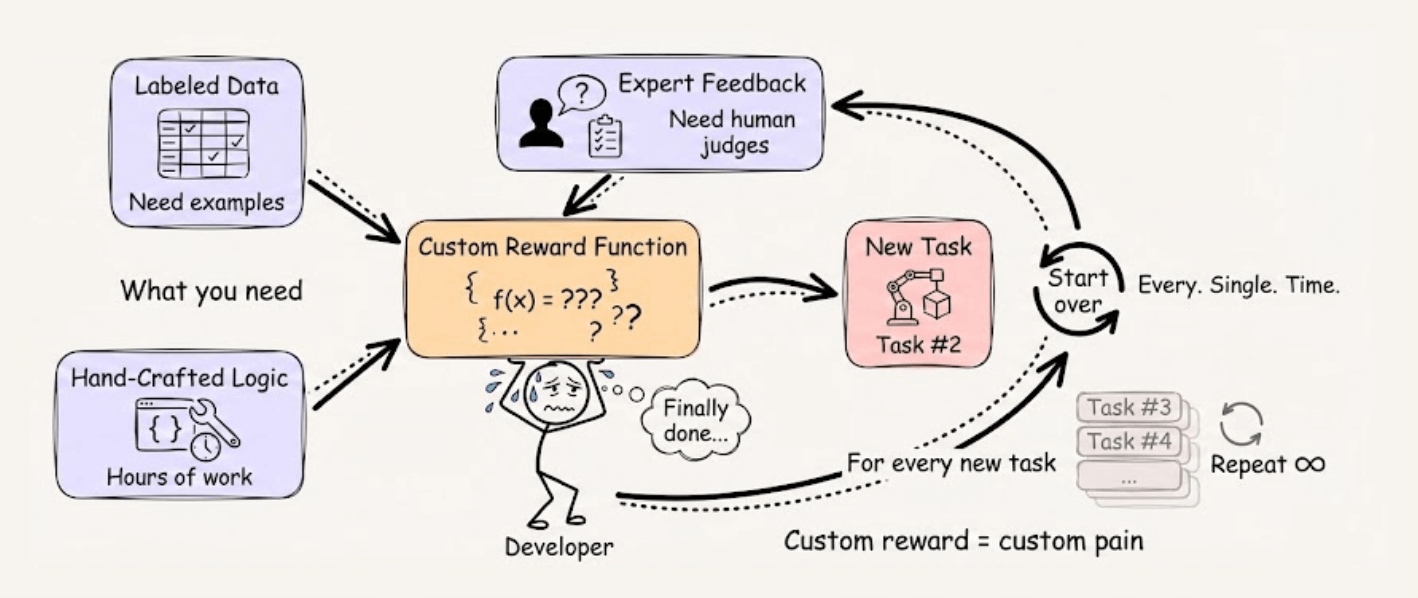

Training LLM agents with RL typically requires writing custom reward functions, which means you need labeled data, expert feedback, or hours spent hand-crafting reward logic for every new task.

RULER from OpenPipe (open-source) takes a different approach. Instead of scoring each trajectory in isolation, it asks an LLM judge to rank multiple trajectories against each other.

This works because relative comparison is fundamentally easier than absolute scoring, and since GRPO normalizes scores within each group anyway, only the relative rankings matter.

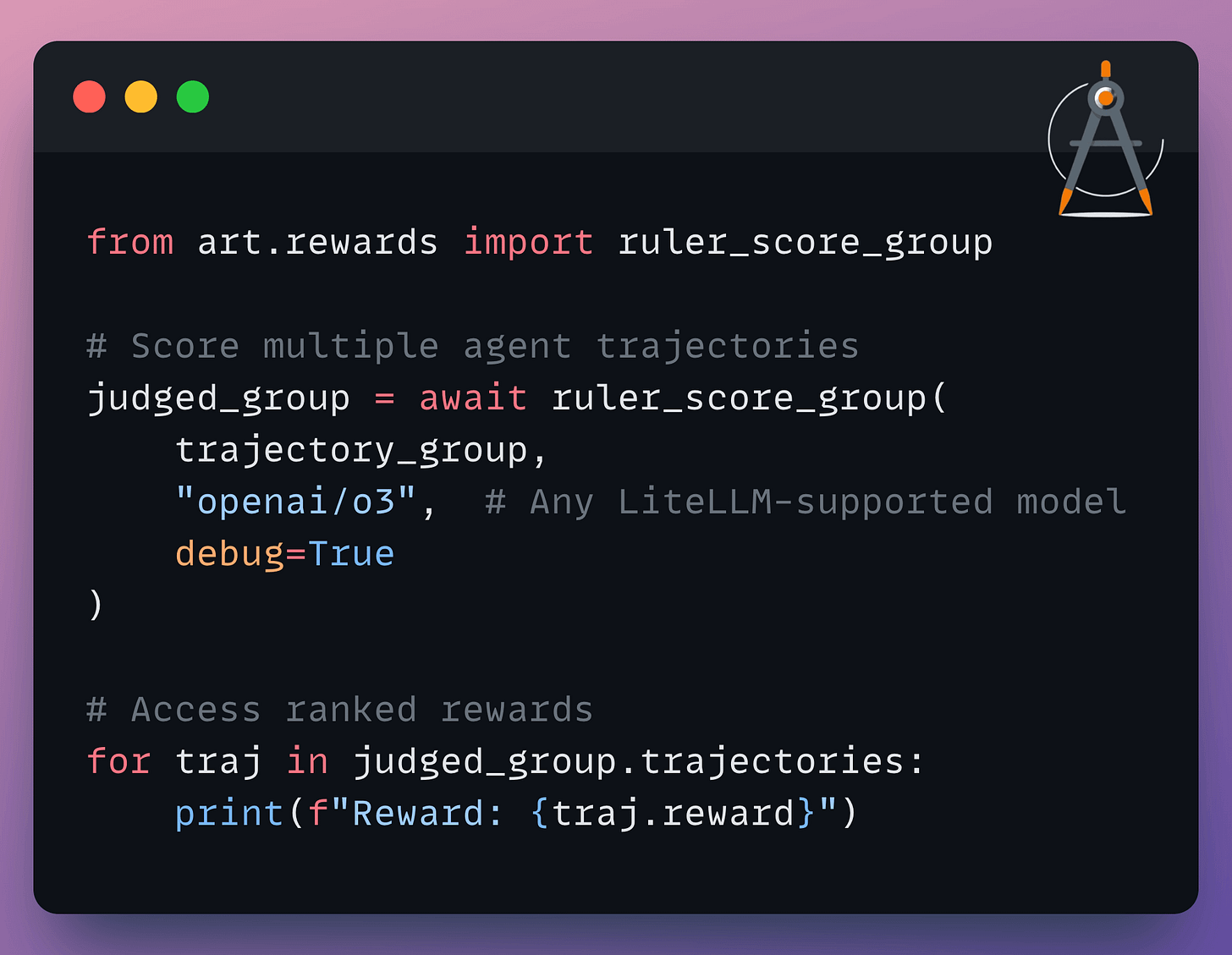

The implementation is straightforward:

You can use any LiteLLM-supported model as the judge, add custom rubrics for specific evaluation criteria, and it automatically caches responses to avoid redundant API calls.

It’s a practical way to get started with agent training without the usual reward engineering overhead.

You can find the OpenPipe ART GitHub repo here →

4 parallel processing techniques in Python

To unlock true parallelism, Python developers use 4 distinct techniques: threads, multiprocessing, coroutines, and subinterpreters. Each solves different problems, and choosing the wrong one wastes hours of effort.

Let’s understand these 4 approaches today.

Understanding the problem

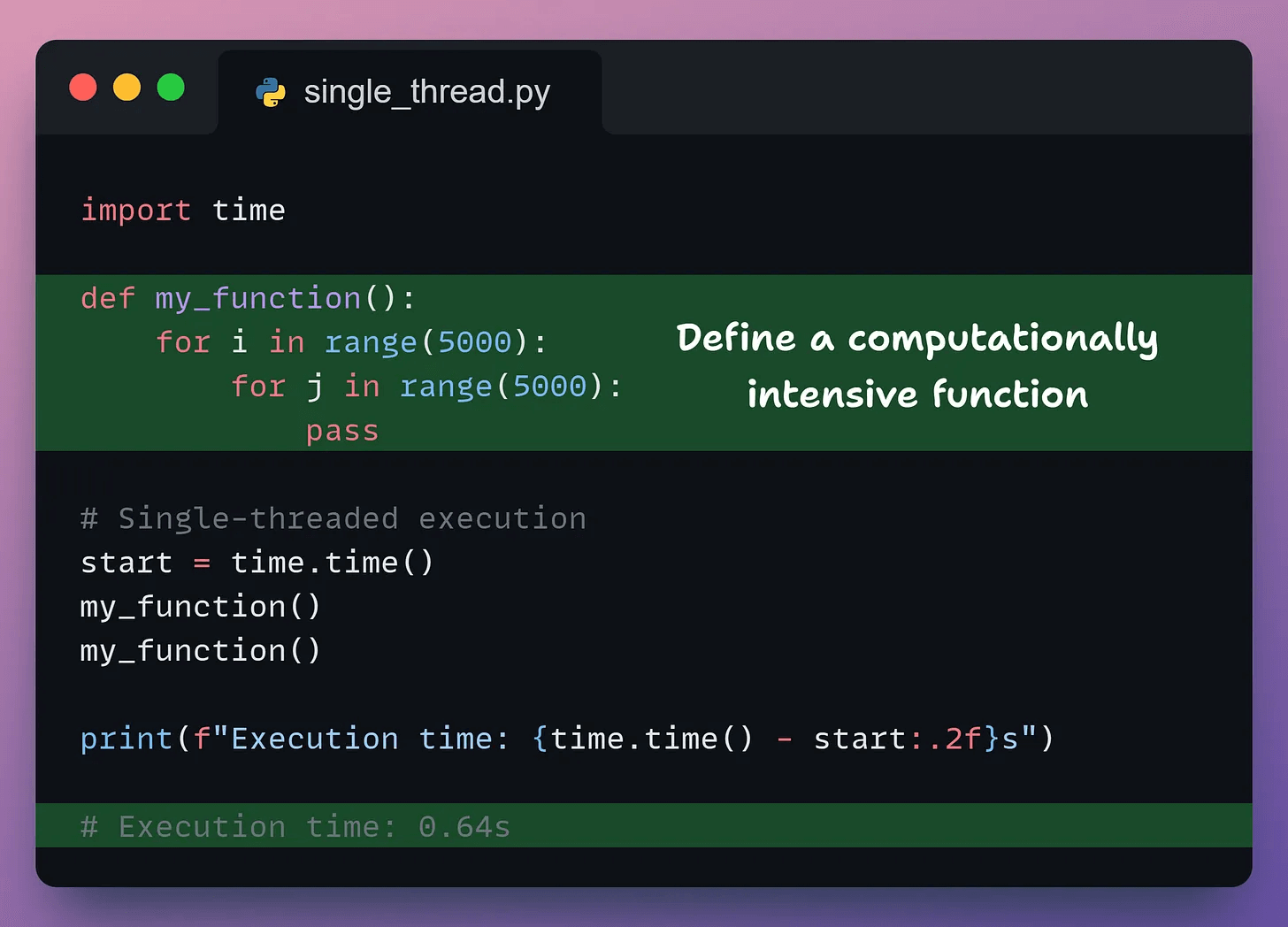

By default, Python executes code on a single CPU core, even if your machine has 8 or 16 available.

The reason: the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL).

The GIL ensures only one thread executes Python bytecode at a time, preventing race conditions but blocking true parallel execution for CPU-bound tasks.

Python offers different approaches to handle this; some bypass the GIL entirely, some work within its constraints, and some offer different execution models.

Let’s explore each one.

The 4 Techniques

We’ll compare these techniques on a simple CPU-bound task.

Here’s our baseline single-threaded code:

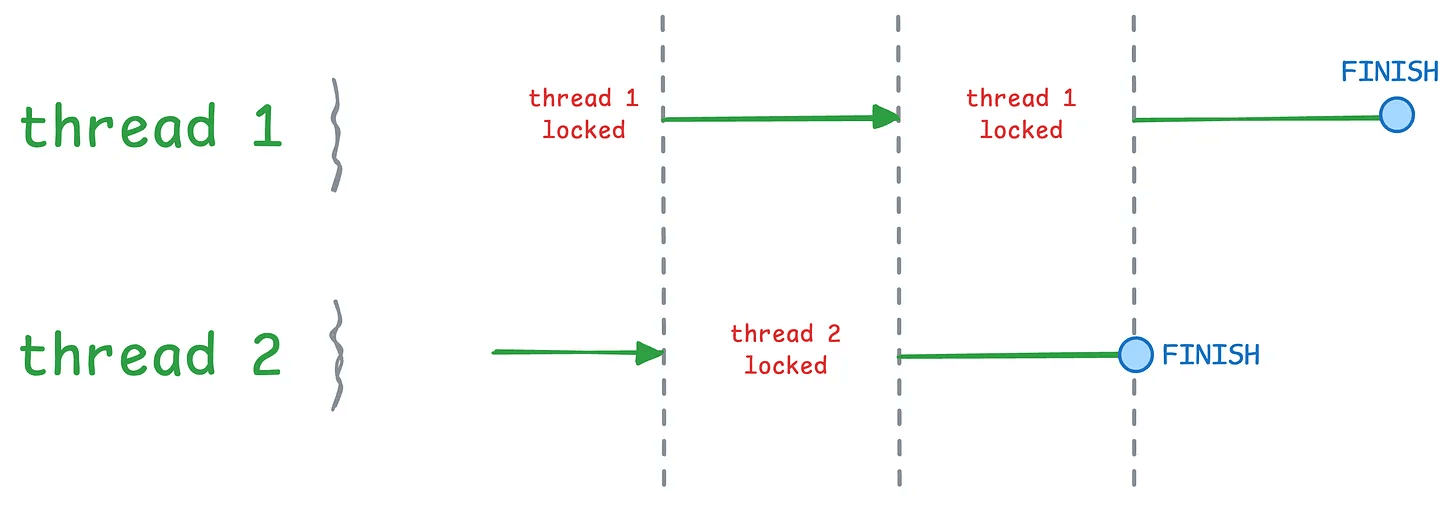

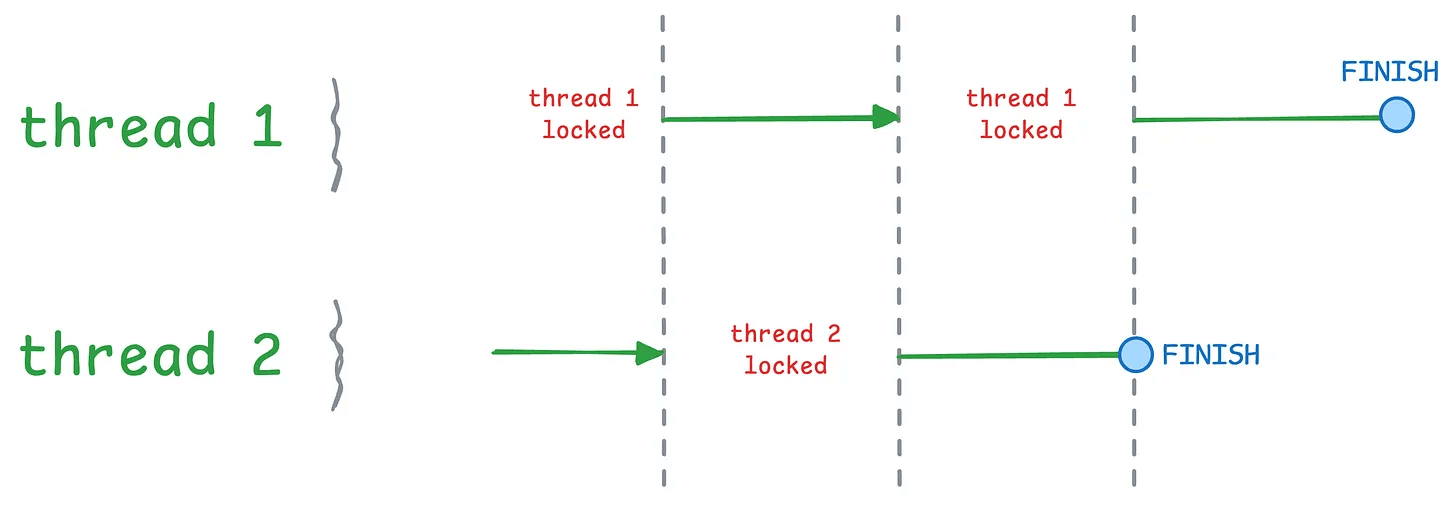

1) Threads

Threads are lightweight workers sharing the same memory space within a process. But despite having multiple workers, only one can execute at any time due to the GIL.

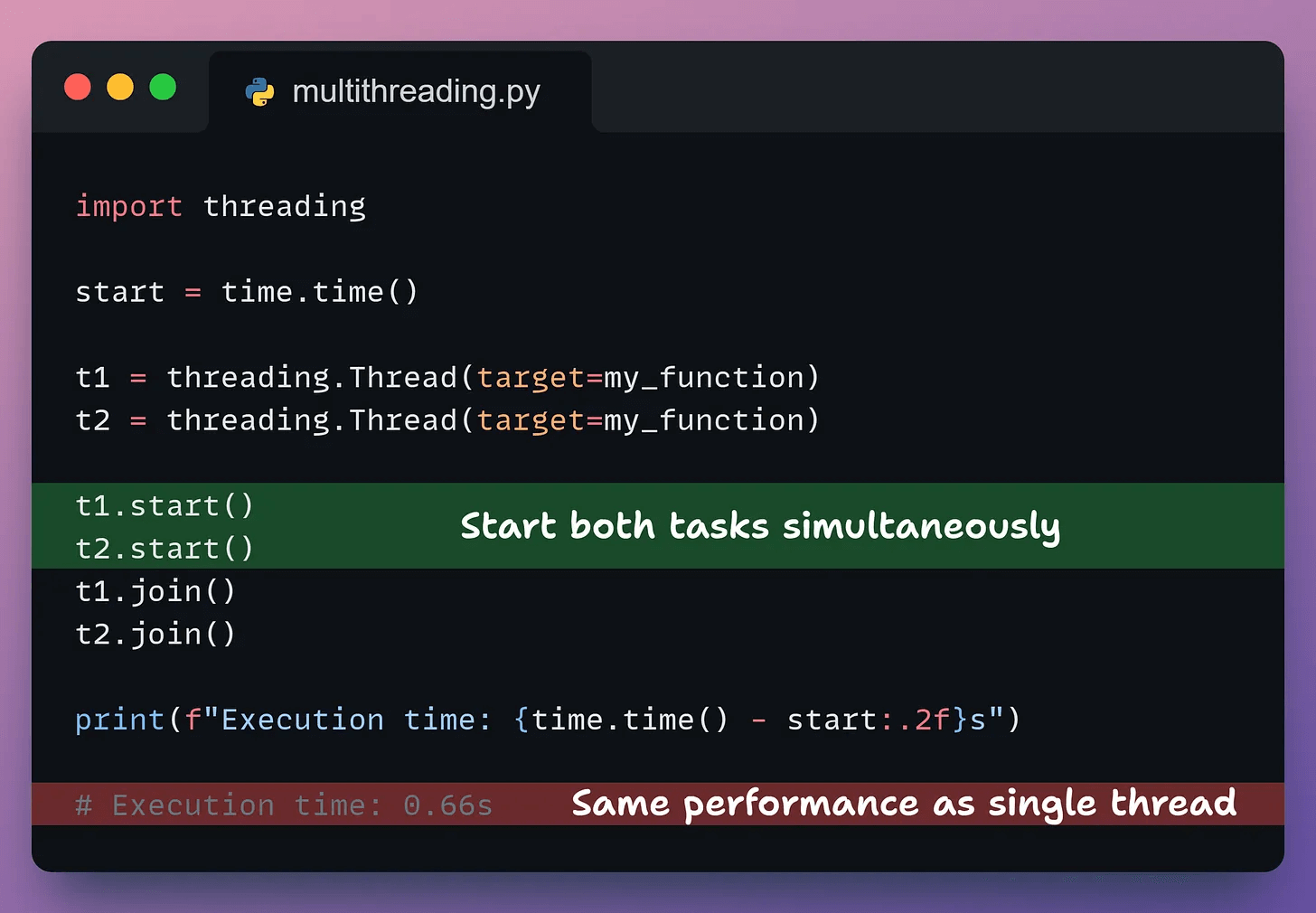

Let’s look at the code example for multithreading:

We create two threads, assign each the task, start them, and wait for completion using join().

Result: no speedup.

The GIL ensures only one thread executes at any moment. They take turns, running sequentially.

The GIL releases during I/O operations, making threads effective there. But for CPU-bound work, threads don’t help.

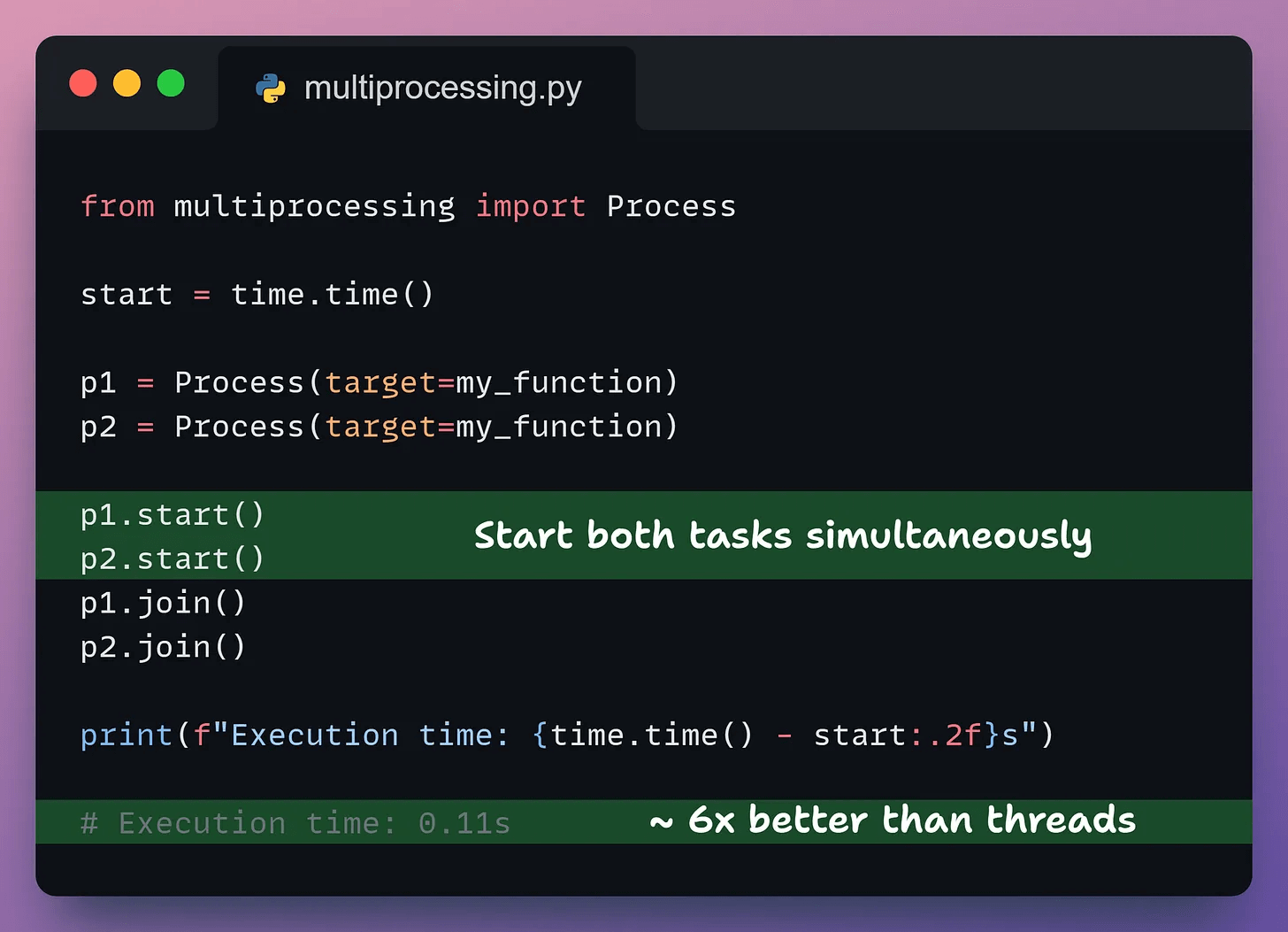

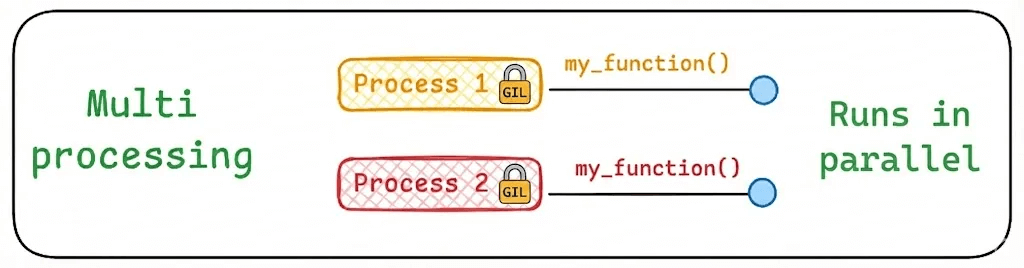

2) Multiprocessing

Each process has its own memory space and its own GIL. This isolation enables true parallel execution on different CPU cores.

Let’s look at the code for multiprocessing:

The two processes run simultaneously, giving us nearly 6x speedup.

There are caveats though.

Startup overhead: Creating processes takes longer than threads. For tasks taking only milliseconds, the overhead outweighs the gains.

No shared memory: Exchanging data requires inter-process communication (pipes, queues), adding complexity and potential bottlenecks.

3) Coroutines

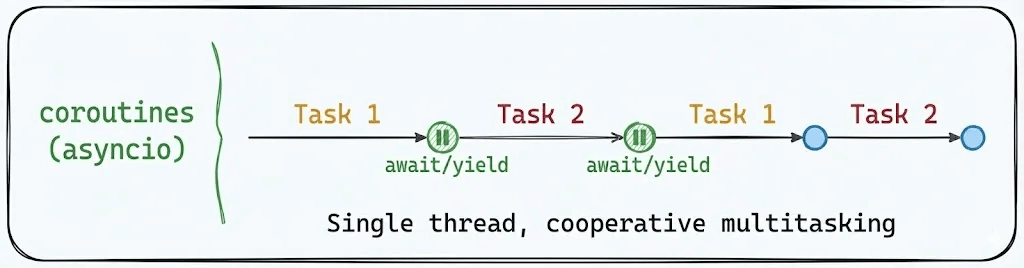

Coroutines enable cooperative multitasking within a single thread. Instead of the OS deciding when to switch, your code explicitly yields control at await points.

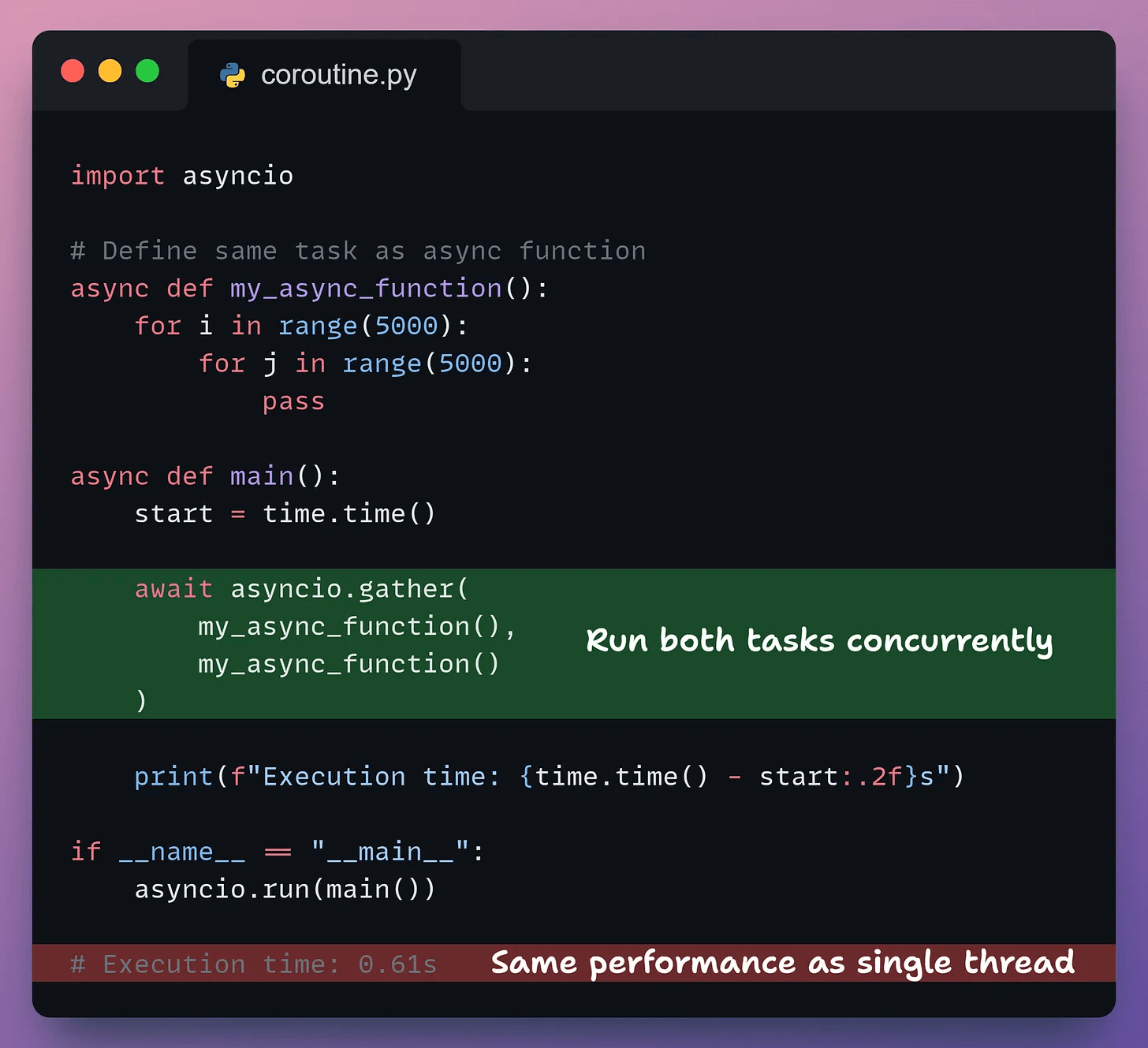

In the code below, we define an async version and use asyncio.gather() to run both tasks concurrently.

In this specific case, it produces no benefit for CPU-intensive tasks.

This is because Coroutines only switch when you explicitly await. Our CPU-bound task never yields, so both run sequentially.

Note: Coroutines enable concurrency (handling multiple tasks) but not parallelism (executing simultaneously). We include them because developers often confuse the two.

Coroutines shine when waiting on external resources, like APIs, databases, and file systems. But for pure computation, there’s no advantage.

4) Subinterpreters

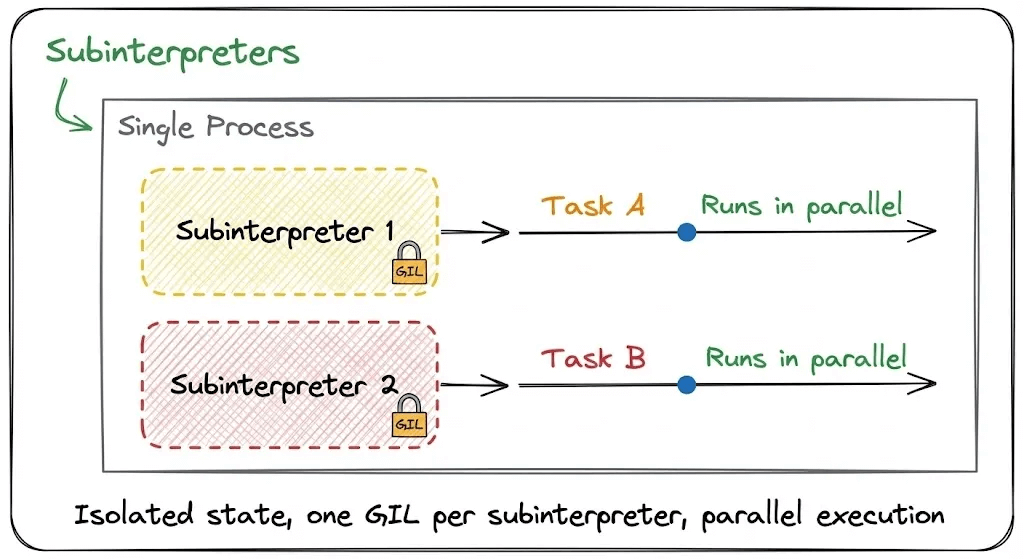

Multiprocessing offers parallelism but is slow and resource-heavy. Threads are fast but blocked by the GIL.

Subinterpreters offer a middle ground.

These are isolated execution environments within a single process. Each has its own memory space and GIL, enabling safe parallelism with less overhead than multiprocessing.

They’re safer than threads because they don’t share global objects by default, preventing memory corruption issues.

They are available from Python 3.12 onwards.

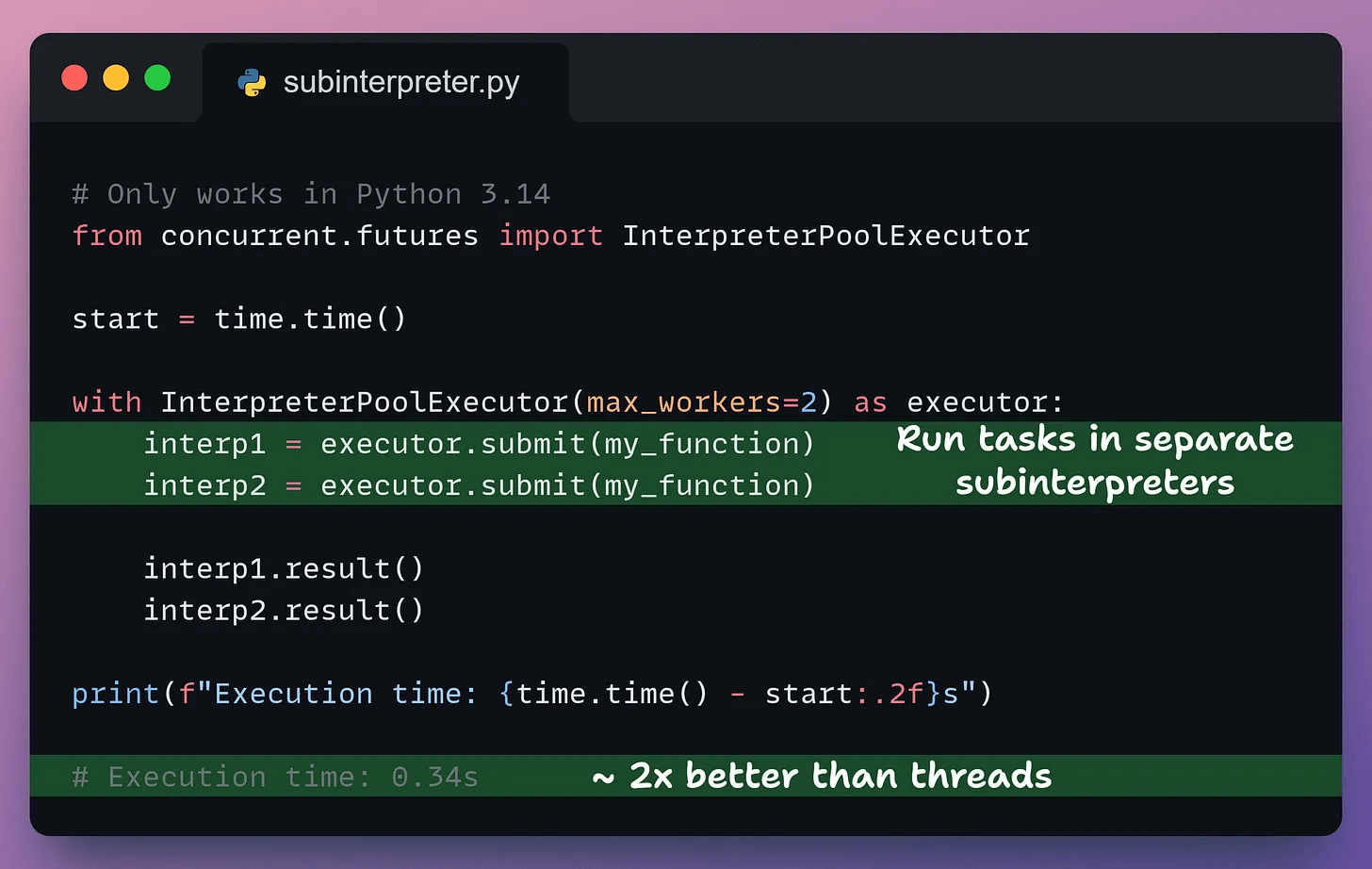

Let’s see them in action:

InterpreterPoolExecutor manages a pool of subinterpreters. We submit tasks using submit(), and result() waits for completion.

This results in nearly 2x speedup compared to threads, with less overhead than separate processes.

Note: The

InterpreterPoolExecutorAPI requires Python 3.14 for the promised performance gains. Earlier implementations (3.12, 3.13) don’t achieve true parallel speedup. Subinterpreters remain experimental and aren’t yet recommended for production.

Only multiprocessing and subinterpreters delivered true parallelism for CPU-intensive tasks.

Threads and coroutines showed no speedup since the GIL prevented them from using multiple cores.

Free-threaded Python

Python 3.13 introduced free-threaded builds where you can disable the GIL entirely.

With GIL disabled:

Threads become viable for CPU-bound work, achieving performance similar to multiprocessing.

Multiprocessing remains useful for process isolation and fault tolerance, but not required for CPU parallelism.

Coroutines stay unchanged. They are still about cooperative multitasking, not parallelism.

Subinterpreters lose their main differentiator. They still offer global state isolation, but the performance advantage fades.

That said, free-threaded builds have 10-40% overhead for single-threaded code, and many C extensions assume the GIL exists. We’re in a transition period, so you can expect threads to become the default for parallel work over the next 2-3 years.

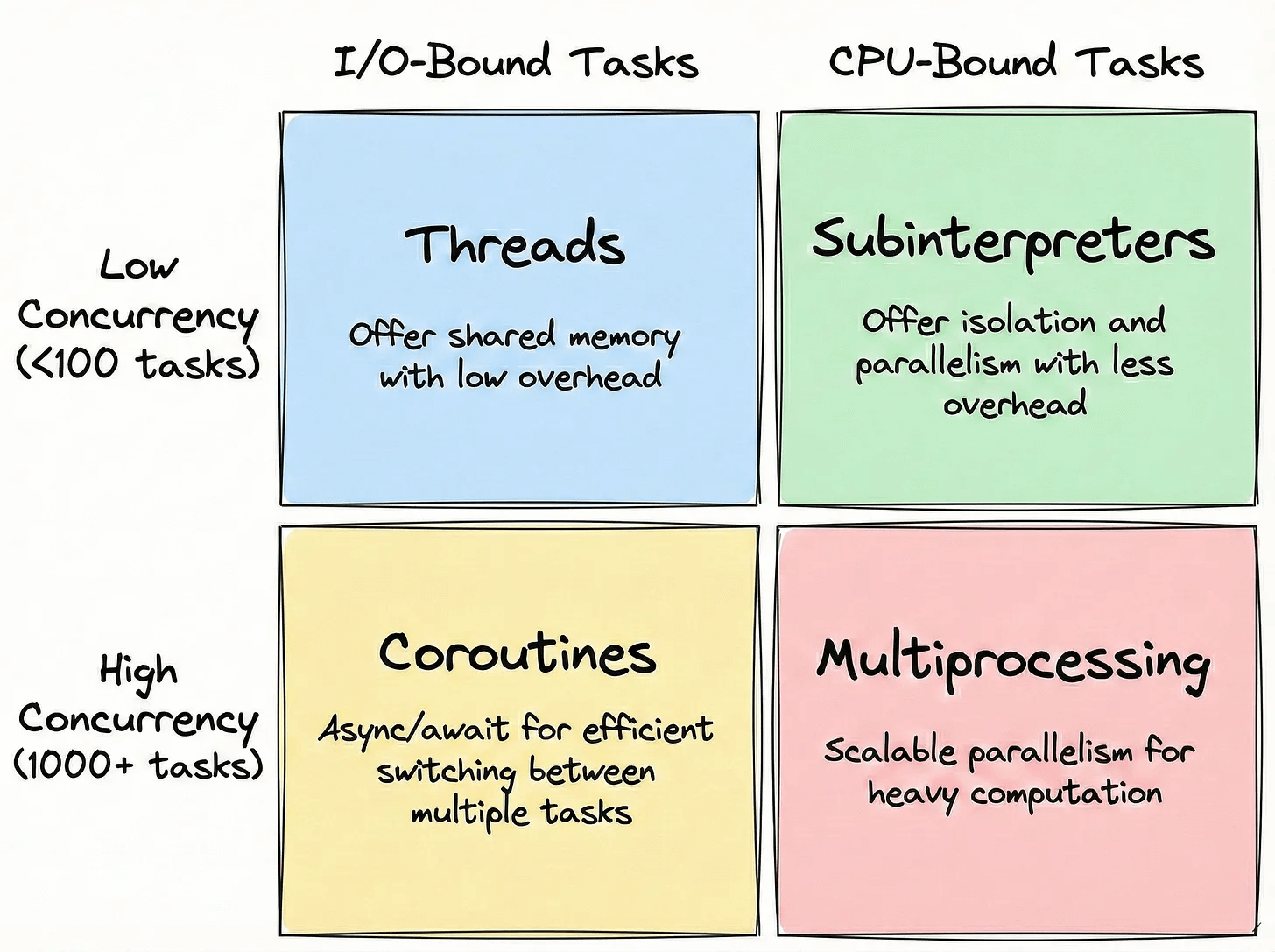

Decision guide

Until free-threaded Python becomes default:

Use Threads when:

Your task is I/O-bound (waiting on files, networks, databases)

You need shared memory between tasks

The overhead of process creation is too high

Use Multiprocessing when:

Your task is CPU-bound and needs true parallelism

You want process isolation for safety or fault tolerance

You can afford the startup overhead

Use Coroutines when:

You’re handling high-concurrency I/O operations (thousands of connections)

You’re building async web servers, scrapers, or API clients

You need efficient context switching for I/O operations

Use Subinterpreters when:

You need CPU parallelism with less overhead than multiprocessing

You want isolated execution environments within a single process

You’re building systems that need safe isolation between tasks

This visual sums it up nicely:

Those are the 4 techniques for parallel processing in Python.

Each technique has its place. Understanding when to use which separates good Python code from great Python code.

👉 Over to you: What other parallelism techniques do you use in Python?

Thanks for reading!